Figure 1: Carbon Dioxide over 8000.000 years (NOAA, 2025)

This warming is not just an environmental issue. It is a systemic risk to our societies, our economies and our health. Climate change is increasingly recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Economic Forum (WEF) as the biggest health challenge of the 21st century. In fact, the WEF’s Global Risks Report shows that climate and nature-related risks dominate the list of the world’s top long-term threats.

Figure 2: Global Risks Perception Survey 2024 - 2025 (World Economic Forum, 2025)

In response, global leaders came together in Paris in 2015 to set clear goals: keep global warming well below 2°C, while striving to limit the rise to 1.5°C. To achieve this, emissions must peak no later than 2025 and fall by 43% by 2030. The European Union translated this into law with the European Green Deal (2019), targeting a 55% reduction by 2030 compared to 1990, and full climate neutrality by 2050. And yet, progress is mixed. About 80% of global energy still comes from fossil fuels, and most large energy companies continue to funnel investment into oil and gas. At the same time, however, there is momentum: in 2022, a record $1.6 trillion was invested in renewable energy, 60% more than fossil fuels, with renewables investment growing by around 15% annually. The transition is underway, but too slow given the scale of the challenge.

Health on the frontline of climate change

Hospitals and health systems are already feeling the strain of a warming planet. According to the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change (2025), heat-related illness and mortality are rising rapidly. Over the past two decades, deaths linked to extreme heat in Europe have quadrupled, with elderly and infants among the most vulnerable during heatwaves. And this is only the beginning: if global warming continues its current path, heat-related mortality is projected to increase a further threefold by 2100 under a 3 °C scenario.

Yet mortality figures only tell part of the story. Every heatwave also brings a surge in illness. Emergency departments across Europe consistently report spikes in patients suffering from asthma, heart and kidney conditions, dehydration, and even acute mental health problems. These patterns show that the health burden of climate change is already present, not a distant concern.

Figure 3: Projection of heat-related mortality (The Lancet Countdown, 2024)

Moreover, a 2025 systematic review by Lakhoo et al. about maternal, foetal and neonatal health, found that for every 1 °C increase in ambient heat exposure the odds of preterm birth rose by roughly 4%, and during heatwaves the odds rose by 26%. High vs low heat exposure was associated with ~48% higher odds of congenital anomalies, and obstetric complications during heat waves rose by ~25%. The risk is especially pronounced in low-income settings: in such countries the odds of preterm birth under high heat exposure were ~1.61 times those in lower-exposure settings, compared to ~1.11 in high-income countries.

At the same time, climate change is reshaping the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Warmer temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns create favourable conditions for pathogens and their carriers to expand into new regions. The Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), capable of transmitting dengue and chikungunya, is spreading rapidly across Europe,[BT4] and the West Nile virus has established itself in areas where it was previously unknown. In the past three years, the long-predicted rise in these arboviral infections in Europe has begun to materialise, with diagnoses increasing along an exponential curve, even though absolute case numbers remain relatively low.

Figure 4: Climate suitability for the transmission of Dengue (The Lancet Countdown, 2025)

Vibrio bacteria, thriving in warmer coastal waters are being detected with increasing frequency in northern Europe, causing gastrointestinal and wound infections. Malaria and other vector-borne diseases are also expected to expand their geographic range in the coming decades.

Figure 5: Climate suitability for the transmission of Vibrio (The Lancet Countdown, 2025)

Food systems are under growing strain. UN-agencies report that food insecurity and malnutrition have significantly worsened in recent years, driven by climate extremes, economic shocks, and conflict. The WHO explicitly warns that climate change disrupts food systems—posing one of the most serious indirect threats to human health, especially for vulnerable populations. And then there are the extreme weather events themselves. Rising sea levels, wildfires, hurricanes, and floods are no longer rare or unpredictable “acts of nature”, they are now foreseeable consequences of a warming climate, and they pose direct, mounting risks to health systems.

Healthcare’s own climate footprint

Healthcare is one of the most essential pillars of modern society and like every major sector it leaves a significant environmental footprint. Far from being an exception, hospitals and health systems mirror the same energy and resource dependencies that drive emissions in other industries. According to research by Health Care Without Harm and Arup, the global healthcare sector is responsible for around 5% of total greenhouse gas emissions, placing it on par with the world’s fifth-largest emitting country. In Western Europe, this share is even higher, with healthcare accounting for roughly 5–8% of national emissions in countries such as France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

These emissions stem from multiple core sources. Hospitals consume vast amounts of energy for heating, cooling, lighting, and powering life-saving devices. They rely on transportation networks for patient and staff travel and the supply chains delivering medical products. Pharmaceuticals and single-use medical goods require carbon-intensive manufacturing and disposal. Healthcare waste, both hazardous and non-hazardous, adds further emissions and environmental burden.

Adding to this is the hidden toll of pharmaceutical pollution. According to several studies, strikingly around 50% of dispensed medications end up unused. When improperly disposed, these pharmaceuticals risk entering waterways and soils, where a global survey of over 1,000 river sites found that pharmaceutical contaminants threatened human or environmental health in more than a quarter of sampled

Why hospitals must act now

Regulation, reporting & accreditation

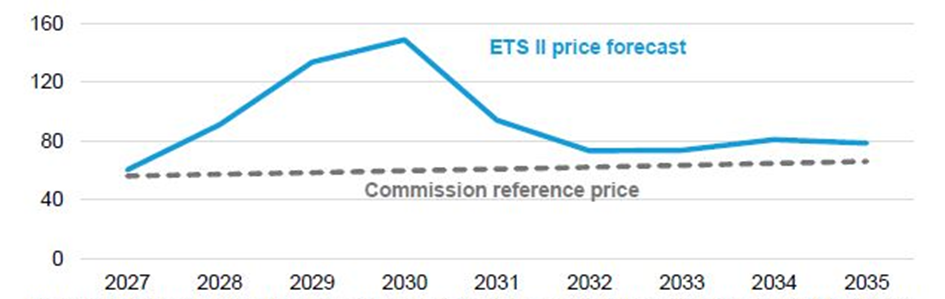

The urgency for hospitals to address their environmental footprint arises from two converging forces. On the external side, regulations are tightening. The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS2) will expand (most likely in 2028) to cover all fossil fuels used in transport and buildings. Hospitals still reliant on fossil energy will face rising costs as the carbon price, around €80 per ton of CO₂, is applied more broadly to heating and transport. Reducing fossil-fuel dependence is therefore both an environmental imperative and a financial strategy.

Figure 6: Forecast ETS2 emissions allowance price (€) per metric ton of CO2 (BloombergNEF, 2025)

Alongside this, the regulatory landscape for transparency is also becoming more demanding. Under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), many large “public-interest entities”, including major healthcare providers, are required to publish detailed sustainability disclosures. CSRD does not mandate specific environmental performance, but it does require hospitals to measure, monitor and report their impacts, risks and transition plans. Due to the ongoing Omnibus simplification package, thresholds and timelines may be adjusted, giving certain hospitals more time or modified criteria. Nevertheless, even smaller hospitals that will be out of the future direct scope increasingly face data requests from insurers, parent organisations or suppliers that must report under CSRD.

At the same time, the financial sector is aligning with this shift: banks and investors increasingly expect credible ESG information before granting credit. Hospitals with robust governance, clear metrics and transparent sustainability plans can secure more favourable loan conditions and reduce long-term financial risk.

Accreditation provides a third external driver. Hospitals competing in quality and international reputation look to certification bodies like the Joint Commission International (JCI). Its 8th edition, developed together with the Geneva Sustainability Center, JCI introduced for the first time a set of sustainability requirements: governance of environmental performance, supply chain responsibility, resource efficiency, green processes, and resilience of infrastructure. Accreditation now extends beyond safety and clinical outcomes to include sustainability as a core element of quality in modern healthcare.

Efficiency and cost savings

Hospitals have also compelling internal motivations to act. At the heart of this is their mission: healthcare exists to protect and promote health. Contributing to environmental degradation undermines that mission and increasingly risks being seen as contradictory to the values of care.

Financial considerations drive internal decision-making as well. Energy costs, waste disposal, and volatile supply markets all strain hospital budgets. Investments in energy efficiency and renewable infrastructure often offer quick returns and operational savings. In the experience of Net Zero Healthcare Impact, and as demonstrated by the National Health Service, sustainability also serves as a powerful lever for cost reduction, cutting inefficiencies, waste, and low-value care. Particularly during the first couple of years working around sustainability, massive cost savings are possible in the Net Zero Healthcare Experience. The NHS Centre for Sustainable Healthcare recently underscored this point in its publication “How the NHS can cut costs and carbon - What if the biggest cost savings come from sustainability?” , highlighting that environmental action and financial performance are now deeply interconnected.

Risk reduction and resilience

Beyond direct operational savings, sustainability strengthens a hospital’s strategic autonomy. European hospitals rely on long, global, and increasingly fragile supply chains for essential medical goods. Circular procurement, reusable systems, and partnerships with local or regional suppliers reduce dependence on volatile international markets and create shorter, more resilient supply chains. This not only protects hospitals from price spikes, shortages, and geopolitical instability, but also stimulates local economies and keeps value creation closer to the community.

Figure 7: Sustainability is a key job-selection factor for young Europeans (EIB, 2023)

Hospitals also have a strong reason to think ahead. Buildings, equipment, and infrastructure last for decades, meaning that today’s decisions will shape their environmental footprint well into the 2040s and 2050s. Ignoring sustainability now risks locking hospitals into outdated, inefficient, or even non-compliant facilities. Those that invest early, however, stay ahead of upcoming regulations, reduce long-term costs, and build greater resilience against future shocks and disruptions.

Reputation

Finally, reputation also remains an important internal driver. Patients and the public increasingly equate institutional responsibility with ecological stewardship. Hospitals that lead in sustainability reinforce public trust and position themselves as forward-thinking care providers. Conversely, those perceived as lagging risk reputational harm in a climate-conscious environment. For many clinicians and staff, knowing that their workplace is actively reducing its footprint enhances professional pride and helps retain a motivated workforce in a sector already struggling with burnout and shortages. European surveys show that staff, particularly younger professionals, place a high value on working in organizations that align with their personal commitment to sustainability.

From challenge to action

Climate and biodiversity loss is the defining health challenge of our time. Hospitals and healthcare systems are already on the frontlines, treating heat-related illnesses, responding to floods, and facing new infectious diseases, while at the same time contributing around 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This dual role highlights both the vulnerability and the responsibility of the sector. By cutting emissions, strengthening resilience, and embedding sustainability into everyday practice, healthcare can protect not only patients but also the planet that sustains them. The tools are already available. What is needed now is clear strategic leadership from hospital executives, backed by committed action from doctors, nurses, and support teams across the system.

The message is clear: for hospitals, climate action is no longer just a moral imperative, it is a strategic necessity. Fortunately, the solutions are ready to implement. The following five immediate steps can help hospitals reducing their environmental footprint of today, while strengthening resilience and safeguarding the continuity and quality of care:

- Measure the full Scope 1–2–3 footprint and key environmental pressures to create a robust baseline for strategy, governance and transparent reporting.

- Embed sustainability into board oversight, risk management and investment planning to meet regulatory expectations and support long-term financial stability.

- Engage clinical teams, staff and suppliers to embed sustainable practices into daily operations and build a culture of resilient, low-impact, high-quality care.

- Prioritise reducing medication waste, single-use material consumption, food waste and energy inefficiencies to deliver rapid emissions reductions and significant operational savings.

- Strengthen procurement and supply-chain design to reduce vulnerability to shortages and increase organisational autonomy.

At Net Zero Healthcare Impact, we help hospitals turn ambition into action. Our dedicated carbon footprint tool allows hospitals institutions to measure emissions across Scope 1, 2, and 3 and identify hotspots. In addition, we also assess other environmental pressures such as the biodiversity impacts of pharmaceuticals entering wastewater. By making the ecological impact visible and measurable, we help hospitals to set priorities, engage their teams, communicate transparently with stakeholders, and unlock millions of euros in savings. The evidence is clear, the tools exist and the moment to act is now. Let us help you from intent to impact.

References

- Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, 2025, How the NHS can cut costs and carbon – What if the biggest savings come from sustainability?

- European Investment Bank, 2023, 76% of young Europeans say the climate impact of prospective employers is an important factor when job hunting

- García-León et al., 2024, Temperature-related mortality burden and projected change in 1368 European regions: a modelling study

- Lakhoo et al., 2024, A systematic review and meta-analysis of heat exposure impacts on maternal, fetal and neonatal health

- Romanello et al., 2024, The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: facing record-breaking threats from delayed action

- Romanello et al., 2025, The 2025 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

- Wilkinson et al., 2022, Pharmaceutical pollution of the world's rivers